THE 19th Century

Attempts to celebrate publicly the anniversary of the passing of the Constitution of 3rd May 1791 were also undertaken during the partitions. All the partitioning powers banned celebration of the anniversary, but it was slightly easier to organise national celebrations in Galicia, or even in the Prussian sector. From the 1880s, progressive Jews from Kraków and Lviv organised evenings devoted to the Constitution. A service was organised in the “Tempel” synagogue in Kraków on the 100th anniversary of its adoption, attended by huge crowds of Poles and Jews. Discussions about the importance of the “Constitution of 3rd May” took place in émigré political circles and among eminent historians connected to the Jagiellonian University (i.e., the Cracow historical school). These resulted from the need to reflect on the future of the nation and the causes of the fall of the Commonwealth. Their fundamental method of battling for Polish independence was through the use of their pens, mainly via the Historical Society, founded in Lviv in 1886. During the years of struggle for Polish independence, the Constitution lived on in people’s memories and the mass demonstrations that took place on the 100th and 125th anniversaries of its adoption helped people commemorate their lost nation, despite the serious repression demonstrators risked within the Russian-controlled territory.

At this point it is worth noting that it was in fact here, in the Kingdom of Poland, as early as 1831, that a text was written which can be considered the first ever draft of a Constitution for a United Europe. Written by Wojciech Bogumił Jastrzębowski during breaks in the fighting for the defence of Warsaw (the battle of Olszynka Grochowska of 25th February 1831) and with final edits on 30th April 1831, this draft was published, not coincidentally, on 3rd May 1831, on the anniversary of the May Constitution. Jastrzebowski’s draft of 77 articles included, among other things, the following:

National laws will guarantee the equality of people who make up one nation, while the guarantee of equality of European nations will be European laws, which are to constitute the basis of an eternal covenant in Europe (Art. 2) and All nations belonging to the eternal covenant in Europe are equally subject to European laws (Art. 12).

After the fall of the November Uprising, in 1832, significant restrictions were imposed on the autonomy of the Kingdom of Poland: the suspension of the constitution, the incorporation of the Polish army into the Russian, the liquidation of the Polish parliament and local authorities. Until the January Uprising of 1863/1864, the Russian authorities successfully suppressed any attempts at resistance from Polish society.

Thousands of Poles were forced to leave their homeland after the November Uprising, going mainly to France. The post-uprising, so-called “great” emigration played an enormous role in the cultural and political life of both countries.

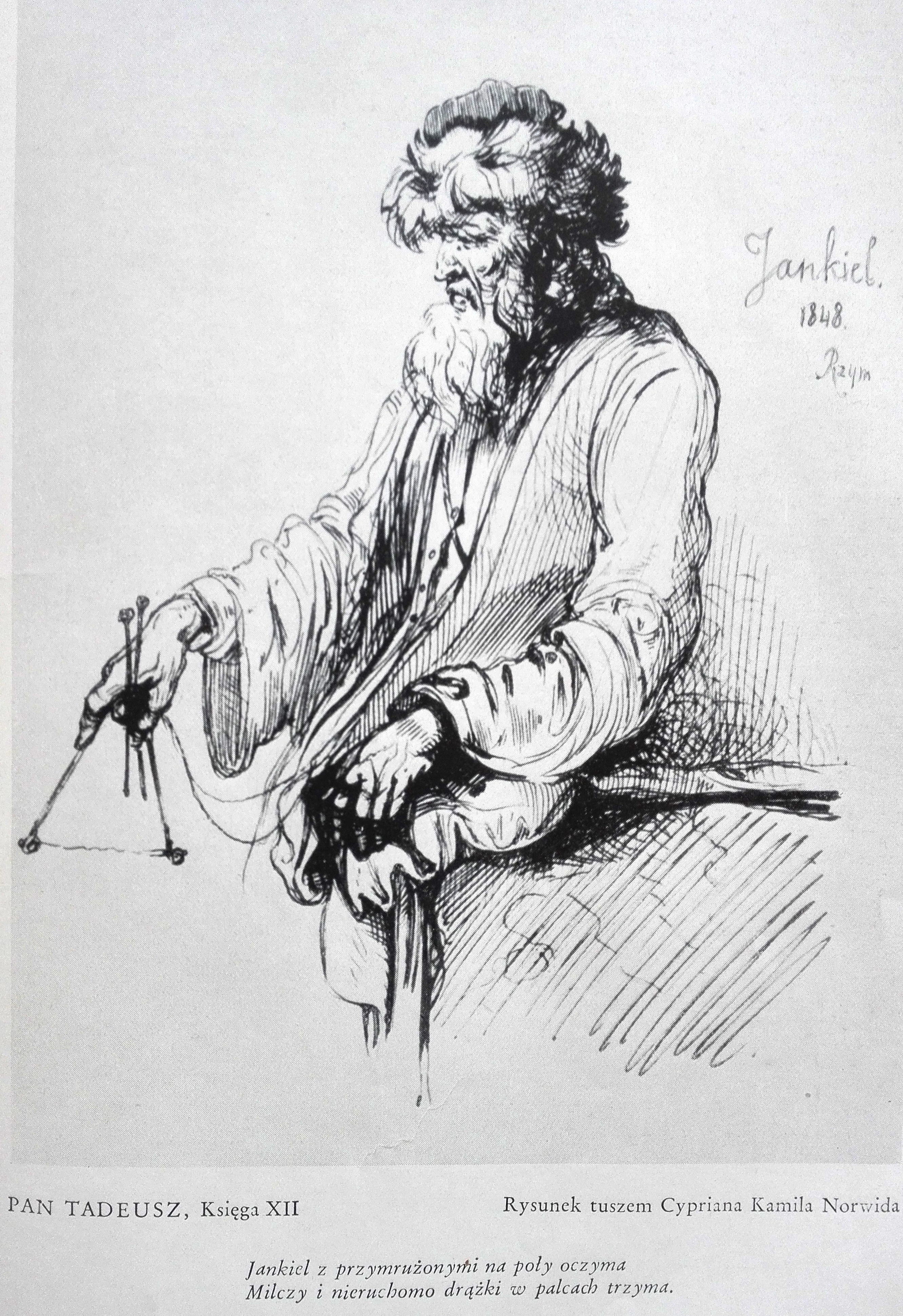

The May Holiday was not forgotten. Adam Mickiewicz referred to it in his Polish national epic “Pan Tadeusz, or The Last Foray in Lithuania”, published in 1834 in Paris. The famous concert of the Jew Jankiel, also known as the “concert to end all concerts”, is a fragment from Book XII of the epic, entitled “Let's make love!” performed on the occasion of Tadeusz's engagement to Zosia. In it, Mickiewicz recalls the historical events preceding the fall of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The five-part concert is a musical illustration of the period from the adoption of the 3rd May Constitution to the formation of the Polish Legions in Italy. The first part refers to the Constitution of 1791 that reformed the political system of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth:

Burst forth a sound as though a whole janissaries’ band

Had become vocal with bells and cymbals and drums.

The Polonnaise of the Third of May thundered forth!

The rippling notes breathed of joy, they poured joy into one’s ears;

The girls wanted to dance and the boys could not stand still –

But the notes carried the thoughts of the old men back into the past,

To those happy years when the Senate and the House of Deputies,

After that great day of the Third of May, celebrated in the assembly hall

The reconciliation of King and Nation;

When they danced and sang “Vivat our beloved King,

Vivat the Diet, vivat the people, vivat all classes!”

Jankiel’s Concert

Drawing: Cyprian Kamil Norwid, 1848 r.

(Source: A. Mickiewicz, Pan Tadeusz: or, The last foray in Lithuania, a story of life among Polish gentlefolk in the years 1811 and 1812, in twelve books)

(English translation: 1917, J.M. Dent, translation in English. pp. 323-324)

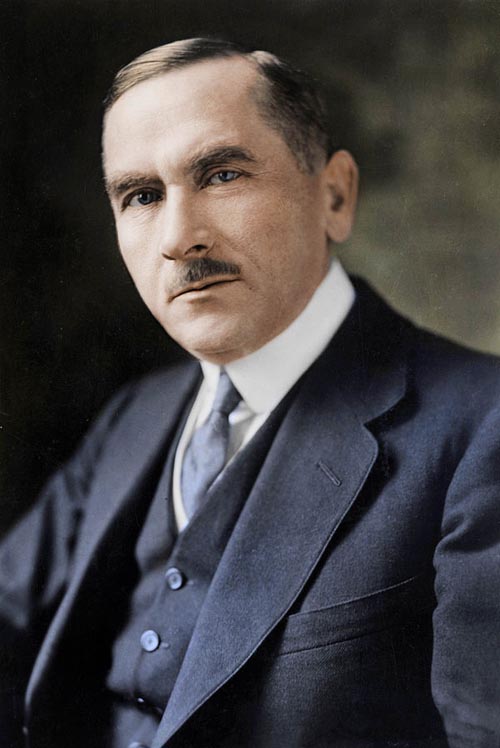

The final years of the 1890s saw the resurgence of a desire for independence in the Kingdom. In early 1887, the Union of Polish Youth (Zet) was formed, supported by its patron from 1888, the Liga Polska (Polish League), created in emigration in summer 1887, comprising members of the older generation of independence activists. In 1888, the Central Committee of the League was established in Warsaw which began to coordinate the work of the league across the partitioned territories. Both organisations were dedicated to restoring Polish independence, through educational activities amongst Warsaw workers and peasants and organising street demonstrations; their great champion was a young Zet activist, Roman Dmowski who, together with his supporters, took over the organisation in 1893, turning the Liga Polska into the Liga Narodowa (the National League).

Roman Dmowski

(Source: Wikipedia)

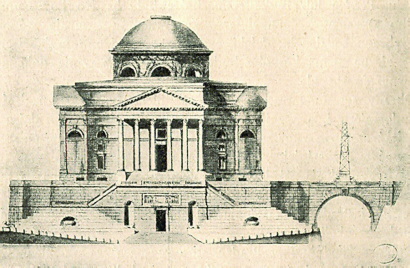

One of the first opportunities to organise a street demonstration was the 100th anniversary of the passing of the Constitution of 3rd May, which fell in 1891. The organisers understood that commemorating national anniversaries was an excellent method of historical education for the youth from Russian-controlled Poland, who had been denied the chance of learning their own history in their ‘Russified’ schools. While celebrations of the 100th anniversary of the Constitution of 3rd May took place pretty much everywhere across [Austro-Hungarian] Galicia, (with academic celebrations and artistic events) and within the Prussian territories ways were found to celebrate the anniversary albeit in a somewhat limited form, (i.e., indoors), in the Russian-controlled territory the appeal to participate in a demonstration hit home mainly among students and one of the important elements of the marches was to march to the Botanical Garden where, in 1792, a foundation stone had been placed under the Church of the Divine Providence. The newspapers of Kraków and Warsaw wrote about this first march in varying tones (including the Kurier Warszwski [Warsaw Courier] from May 1891).

The project of Jakub Kubicki - 1792

(Source: Wikipedia)

Arrests and investigations followed, which also picked up Zet activists, including Roman Dmowski. The way the anniversary had been organised (printing of leaflets calling for participation, commemorative medals), convinced the Russians that there was a secret independence organisation behind the demonstrations. Despite the great difference between the Russian-controlled territory and the rest of the country in their starting points and opportunities to organise political and social activities, the tradition of holding an annual commemoration of 3rd May became a fixed event among Warsaw’s students and, in time, became more than an event just for the young. However, Poles who dared to mark this anniversary publicly were severely punished. In 1892, Stanisław Wiktor Mieczyński, a Polish teacher, translator, and patriotic activist, laid a bouquet of flowers on the anniversary of the Constitution of 3rd May. For this transgression he was arrested in Warsaw by the Russian secret police and sentenced to three years’ exile in Odessa.

Stanisław Mieczyński

(Source: Wikipedia)

Over the following years the media reported the scuffles and arrests in Warsaw, where academic and intelligentsia circles were very active; less so in the provinces. The police arrested people caught tossing bouquets of flowers into the ruins of the Church of Divine Providence in the Botanical Garden, as they organised coordinated roundups of youth on Warsaw’s streets. Over time the demonstrations were joined by an increasingly diverse groups of society. During the years of revolution, the pressure inevitably increased and demonstrations were only permitted to within the limits of public order. After 1907, the 3rd May celebrations became only symbolic in nature. The revolutionary theme became weaker and, in turn, the authorities felt no need to intervene. The annual celebration of the Constitution of 3rd May only started to be marked again in 1916.